© 2015-Present ThePunishmentChannel.com

Enslaved Africans

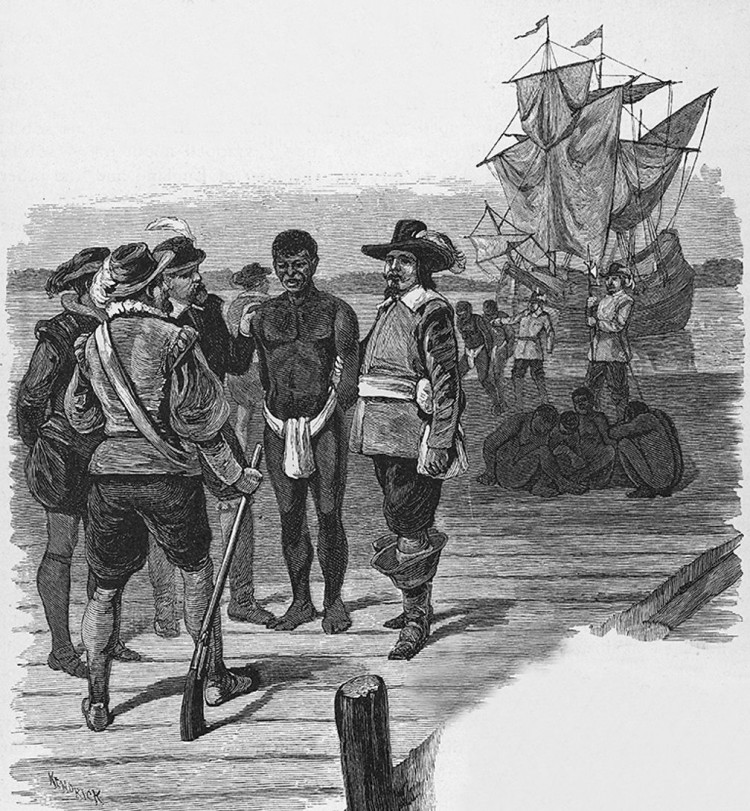

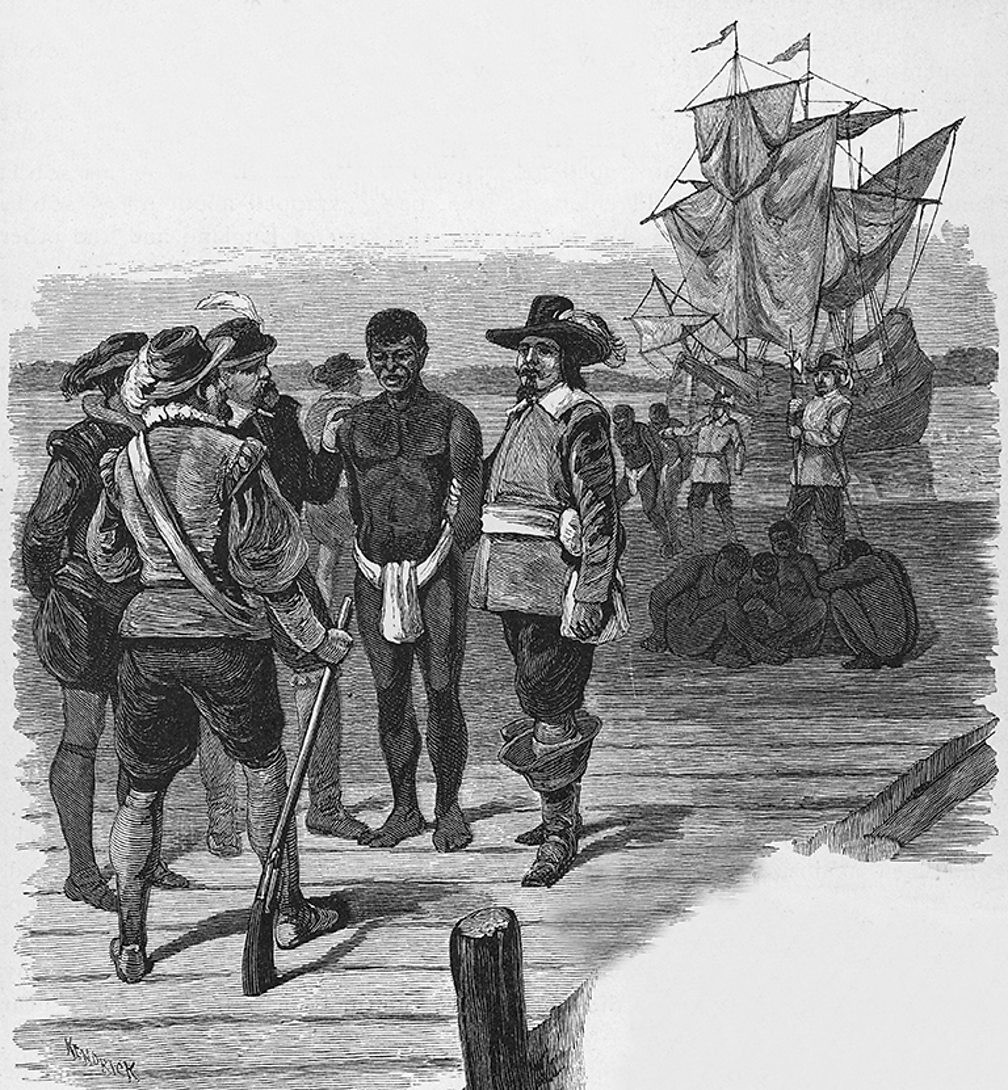

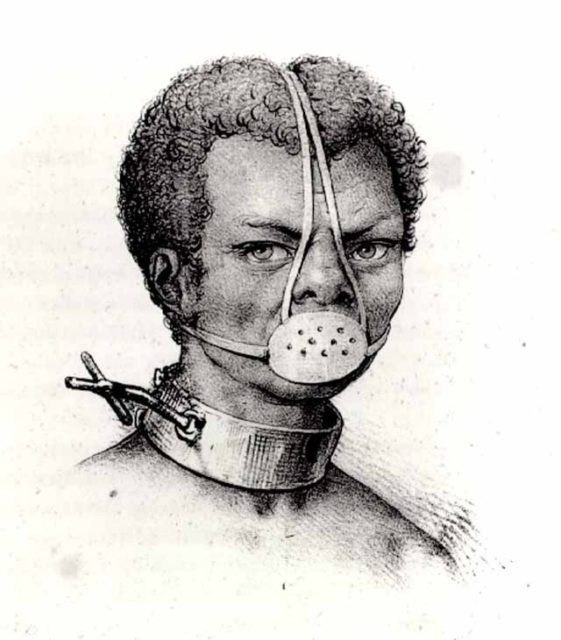

The transatlantic slave trade stands as a dark chapter in human history, characterized by the forced migration and enslavement of millions of Africans. Approximately 12.5 million individuals were uprooted from their homes and forcibly transported on slave ships destined for the New World.

Tragically, only around 10.7 million people managed to survive the horrific journey known as the Middle Passage, enduring unimaginable suffering and cruelty. Their ultimate fate was to be sold into bondage on plantations, predominantly dedicated to cultivating crops such as sugar, rice, cotton, and tobacco, across the Americas and the Caribbean.

For a long time, comprehending the true scale of the transatlantic slave trade seemed like an insurmountable task. The vast number of records scattered across geographically dispersed archives made it nearly impossible to accurately measure the trade's full extent.

However, thanks to the collaborative efforts of a technologically savvy initiative known as the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, we now have the ability to grasp the broad outlines and nuanced patterns of this historical atrocity.

Tragically, only around 10.7 million people managed to survive the horrific journey known as the Middle Passage, enduring unimaginable suffering and cruelty. Their ultimate fate was to be sold into bondage on plantations, predominantly dedicated to cultivating crops such as sugar, rice, cotton, and tobacco, across the Americas and the Caribbean.

For a long time, comprehending the true scale of the transatlantic slave trade seemed like an insurmountable task. The vast number of records scattered across geographically dispersed archives made it nearly impossible to accurately measure the trade's full extent.

However, thanks to the collaborative efforts of a technologically savvy initiative known as the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, we now have the ability to grasp the broad outlines and nuanced patterns of this historical atrocity.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has played a crucial role in shedding light on the magnitude of the trade. Through their meticulous research and collaboration with various institutions and researchers, they have collected and organized an extensive amount of data, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of this dark period.

The database provides valuable insights into the numbers of individuals transported, the origins and destinations of the ships, the conditions endured by the enslaved, and the economic aspects surrounding the trade.

The database provides valuable insights into the numbers of individuals transported, the origins and destinations of the ships, the conditions endured by the enslaved, and the economic aspects surrounding the trade.

This remarkable project serves as a testament to the power of collaboration and technology in uncovering and preserving historical truths. By consolidating dispersed information, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has provided scholars, researchers, and the general public with a valuable resource for studying and acknowledging the immense suffering endured by those caught in the grips of the transatlantic slave trade.

As we reflect upon this somber chapter in history, it is vital to acknowledge the enduring impact of the transatlantic slave trade and the ongoing consequences for descendants of those who were enslaved. By confronting the realities of the past and continuing to support initiatives that promote education, understanding, and healing, we strive towards a more just and inclusive future for all.

As we reflect upon this somber chapter in history, it is vital to acknowledge the enduring impact of the transatlantic slave trade and the ongoing consequences for descendants of those who were enslaved. By confronting the realities of the past and continuing to support initiatives that promote education, understanding, and healing, we strive towards a more just and inclusive future for all.

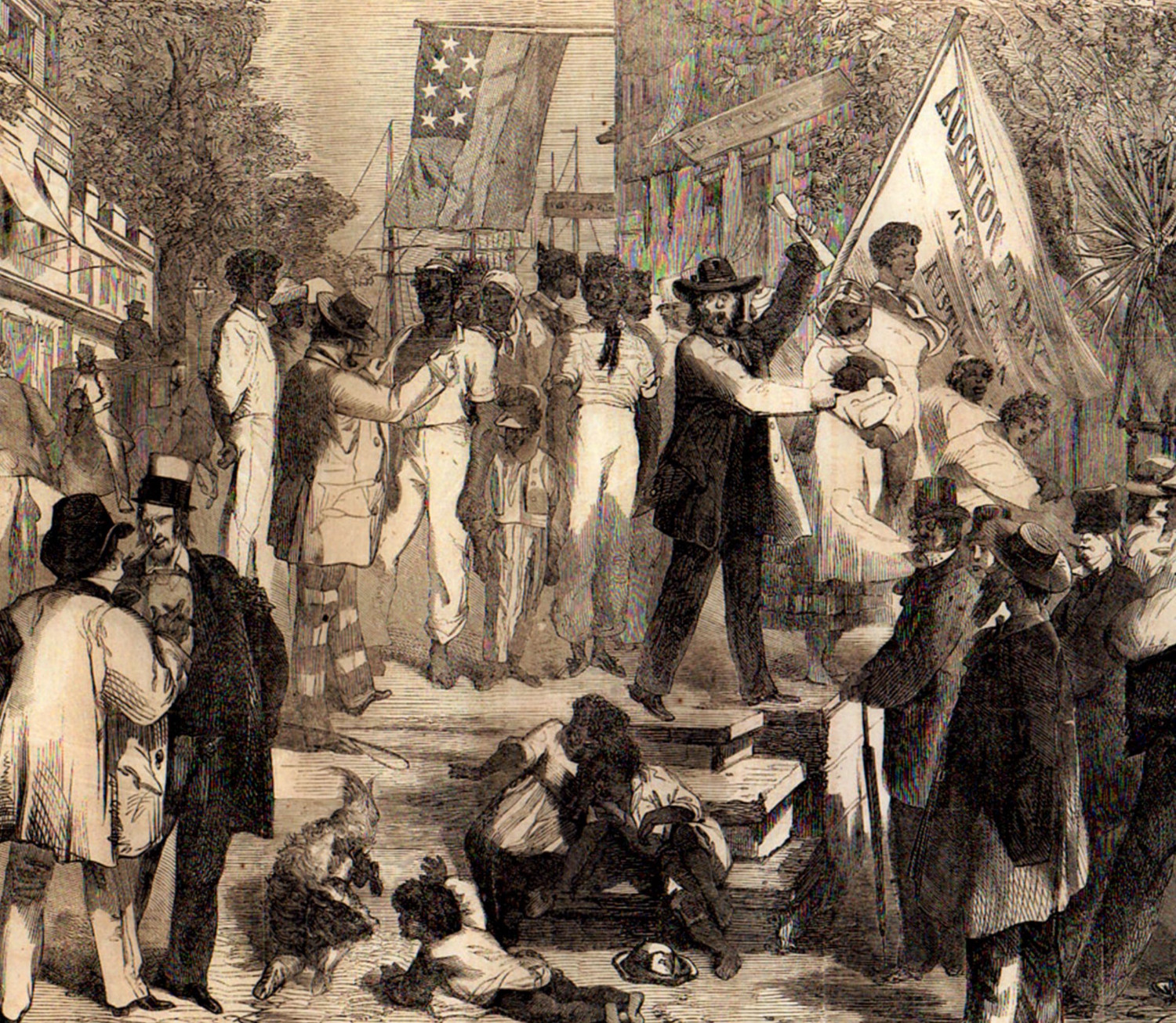

For enslaved African Americans, the ideal of marriage as an enduring lifelong bond was rarely an option. When couples stood before clergy or other officiants, they couldn’t share the traditional, age-old promises of permanent fidelity because their vows had a built-in asterisk: “Do you take this woman or this man to be your spouse—until death or distance do you part?”

Understanding those altered words, couples married with trepidation, fully aware of the turmoil that might result from trying to maintain and nurture their ties while enslaved. Still, they continually took leaps of faith, driven by burning passions to form families of their choosing—and create fundamental human bonds that could help soften the harsh conditions of human bondage.

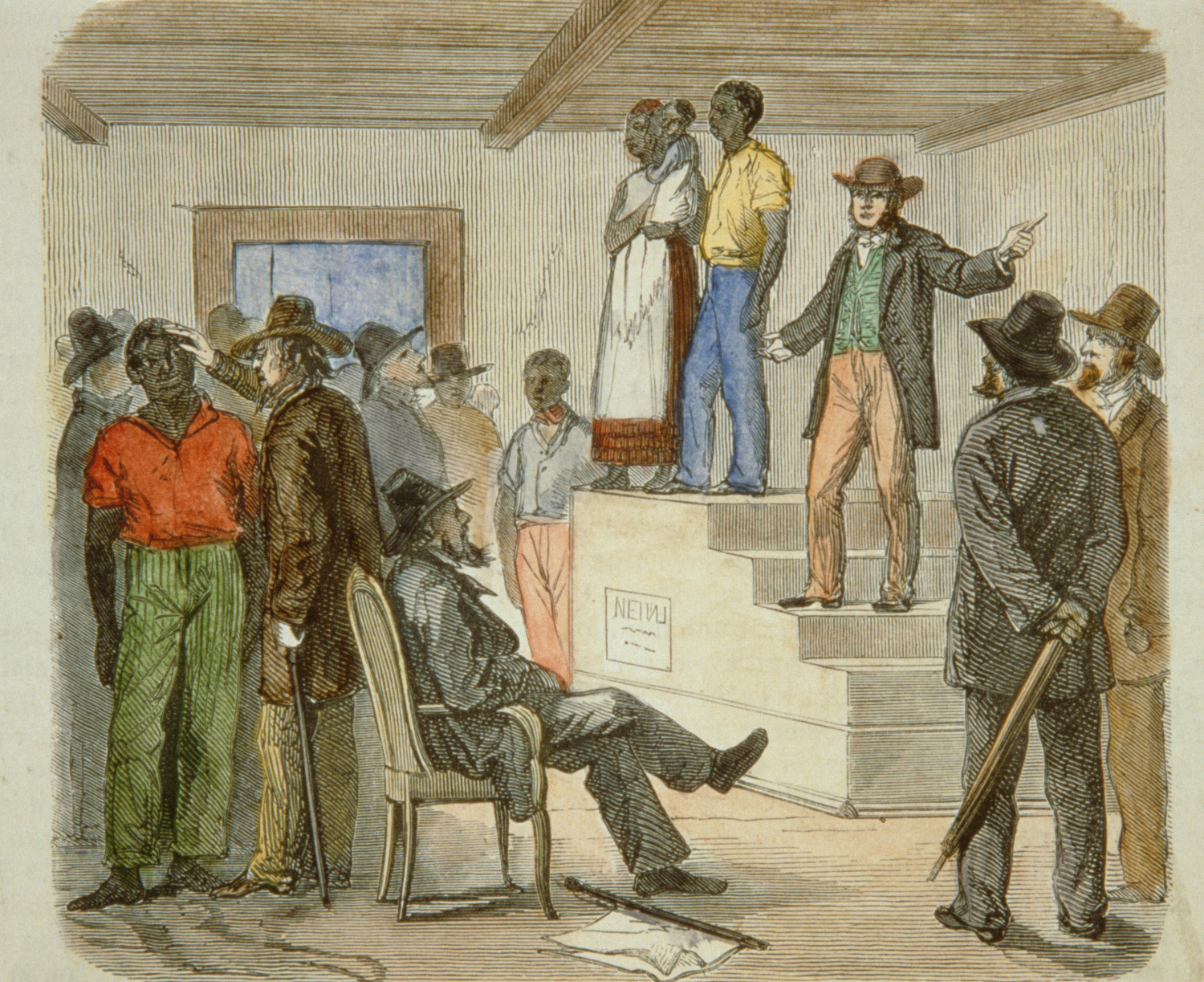

These leaps were necessary because, for nearly 250 years, the vast majority of African Americans were considered chattel property. Within this system, white slaveholders made all the decisions: They determined whether and when enslaved people could wed. They split them apart when finances dictated. They sometimes chose who would marry who. Or brazenly violated enslaved couples’ marriages by forcing the women to serve as their own concubines. And those in political power set laws that made it exceedingly difficult for freed black people to reside for long near their still-enslaved families without being sucked back into the harrowing state of bondage themselves.

Understanding those altered words, couples married with trepidation, fully aware of the turmoil that might result from trying to maintain and nurture their ties while enslaved. Still, they continually took leaps of faith, driven by burning passions to form families of their choosing—and create fundamental human bonds that could help soften the harsh conditions of human bondage.

These leaps were necessary because, for nearly 250 years, the vast majority of African Americans were considered chattel property. Within this system, white slaveholders made all the decisions: They determined whether and when enslaved people could wed. They split them apart when finances dictated. They sometimes chose who would marry who. Or brazenly violated enslaved couples’ marriages by forcing the women to serve as their own concubines. And those in political power set laws that made it exceedingly difficult for freed black people to reside for long near their still-enslaved families without being sucked back into the harrowing state of bondage themselves.

Slavery in the United States

Black slaves played a significant but involuntary role in shaping the economic foundations of the United States, particularly in the Southern region, although their contributions were largely unrewarded. They played a crucial part in labor-intensive industries such as agriculture, where their forced labor was essential for the production of crops. The Southern states relied heavily on enslaved Africans and African Americans to work on tobacco, rice, and indigo plantations during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Black slaves played a significant but involuntary role in shaping the economic foundations of the United States, particularly in the Southern region, although their contributions were largely unrewarded. They played a crucial part in labor-intensive industries such as agriculture, where their forced labor was essential for the production of crops. The Southern states relied heavily on enslaved Africans and African Americans to work on tobacco, rice, and indigo plantations during the 17th and 18th centuries.

This remarkable project serves as a testament to the power of collaboration and technology in uncovering and preserving historical truths. By consolidating dispersed information, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has provided scholars, researchers, and the general public with a valuable resource for studying and acknowledging the immense suffering endured by those caught in the grips of the transatlantic slave trade.

This remarkable project serves as a testament to the power of collaboration and technology in uncovering and preserving historical truths. By consolidating dispersed information, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has provided scholars, researchers, and the general public with a valuable resource for studying and acknowledging the immense suffering endured by those caught in the grips of the transatlantic slave trade.As we reflect upon this somber chapter in history, it is vital to acknowledge the enduring impact of the transatlantic slave trade and the ongoing consequences for descendants of those who were enslaved. By confronting the realities of the past and continuing to support initiatives that promote education, understanding, and healing, we strive towards a more just and inclusive future for all.

The movement to abolish slavery in the British Empire faced significant challenges and resistance from those who profited from the slave trade and the plantation system. However, one of the key figures who dedicated his life to the cause was William Wilberforce. Wilberforce, a British politician and philanthropist, played a pivotal role in mobilizing public opinion and driving political change.

Wilberforce, along with a group of like-minded individuals known as "The Saints," formed an influential force advocating for the abolition of slavery. The Saints consisted of prominent abolitionists, religious leaders, and intellectuals who believed in the moral imperative to end the slave trade. They drew inspiration from their Christian faith, which emphasized the inherent dignity and equality of all human beings.

The political events leading up to the abolition of slavery were marked by fierce debates in Parliament. Initially, the majority of Members of Parliament (MPs) were reluctant to support abolition, primarily due to economic and political considerations. The slave trade was seen as crucial for maintaining the profitability of plantations and protecting the interests of the West Indian plantation owners.

Wilberforce, along with a group of like-minded individuals known as "The Saints," formed an influential force advocating for the abolition of slavery. The Saints consisted of prominent abolitionists, religious leaders, and intellectuals who believed in the moral imperative to end the slave trade. They drew inspiration from their Christian faith, which emphasized the inherent dignity and equality of all human beings.

The political events leading up to the abolition of slavery were marked by fierce debates in Parliament. Initially, the majority of Members of Parliament (MPs) were reluctant to support abolition, primarily due to economic and political considerations. The slave trade was seen as crucial for maintaining the profitability of plantations and protecting the interests of the West Indian plantation owners.